I don’t post on my website or on social media regularly nor do I do so in a chronological fashion. I publish my writings and photos as and when a whim strikes. I enjoy revisiting moments from the past, reviewing the notes I had made and piecing them together. Perhaps it is a subconscious rebel against how fast everything moves around me. I want to savour precious experiences at my own pace.

I love the Ichigo Ichie (“一期一会”) concept that stems from the Japanese tea ceremony. How every encounter only happens once in this life, of impermanent moments.

The “me” who existed on 11 July 2023 is different from the one who’s typing these words now. Today’s “me” has been touched by what transpired that drizzly afternoon in Morioka at Johnny’s Jazz Cafe / Kaiunbashi no Johnny / 開運橋のジョニー.

We had been to Morioka the previous winter, in search of a Nambu tekki tetsu-bin (cast iron teapot).

One month later, Morioka was featured in The New York Times’ annual round-up of 52 places to visit. It was put forth by Craig Mod, a long-time resident of the Land of the Rising Sun. That was how we learned of Morioka’s famed jazz kissaten.

After the pandemic, we had become interested in Japan’s niche phenomenon of jazz kissaten. Often referred to by its abbreviated form of “kissa,” kissaten is the Japanese version of a cafe where coffee is served alongside pasta and toast. Jazz kissa is a subset of kisseten.

However, we did not know of Johnny’s and were intrigued to learn more after reading about it in Craig Mod’s article. Plus, it was a good excuse for us to return to Morioka to continue our search for a Nambu tekki tetsubin.

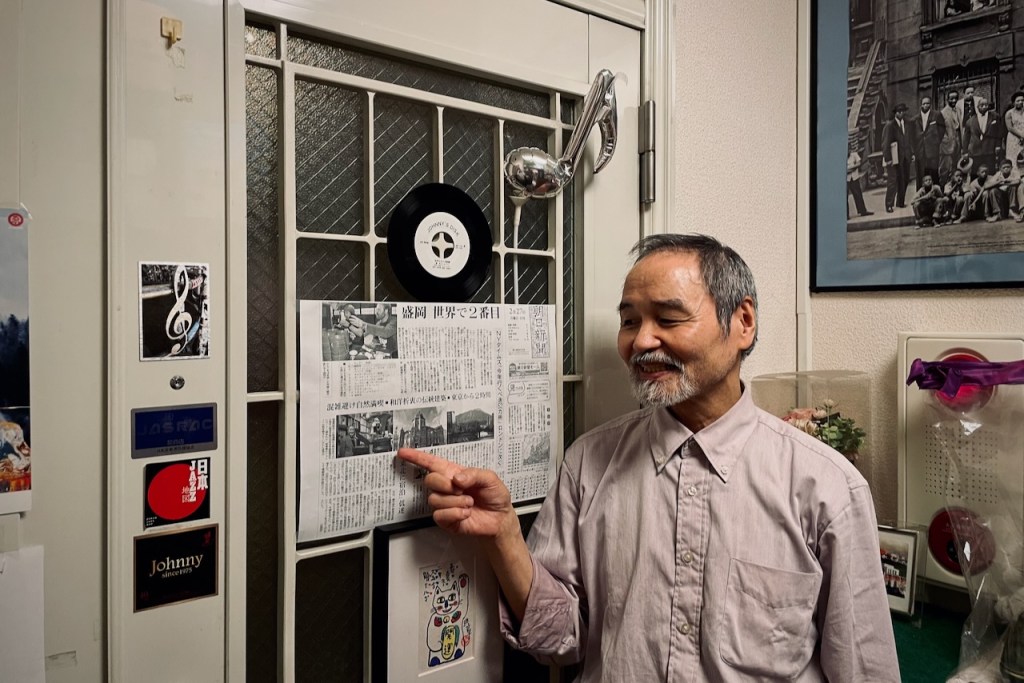

We bumped into the proprietor, Ken Terui, at the lobby of the low-rise building in which Johnny is housed. He was on his way out. Upon realising that we were headed to his shop, he told us, in halting English, to go up and he would be back shortly.

We did as we were told. There was no one inside. It felt like we were intruding as it felt like such a personal space.

We had entered a treasure trove for jazz lovers. One that’s tinged with nostalgia.

Tidy shelves lined with records. Gramophones, amplifiers, and speakers alongside bottles of whisky. A fax machine next to posters featuring jazz pianist, Toshiko Akiyoshi. A vintage clock above a giant Minnie Mouse plush toy. In a corner, a Tiffany lamp with its shade askew.

Unlike most other jazz kissas in Japan, Johnny’s focuses on Japanese jazz. Terui is a super fan of the Japanese jazz pianist, Toshiko Akiyoshi. Her name and works were plastered all over the place. His eyes gleamed as he shared how he had invited her to perform in Rikuzentakata in 1980. In fact, he spearheaded the creation of Toshiko Yoshiyoshi Jazz Museum in the city which debuted during the pandemic.

Opened in 2001, Johnny’s in Morioka is Terui’s second jazz kissa. He had opened the original Johnny in 1975 with his former wife, Yukiko, who continued to run it after they separated in 2004. The name was inspired by a novel “Farewell, My Johnny” by Hiroyuki Itsuki. Located in Rikuzentakata, it was destroyed during the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. Swept away in the tsunami were thousands of records, including rare Japanese recordings. Johnny was famous as the “only Japanese-Jazz expert shop in Japan” (source: Gateway to Jazz Kissa – Vol. 1).

As we sipped on our coffee, Terui showed us his various projects. Including a CD of the live recording of Akiyoshi in 1980, which is “the best” of his productions.

He brought over a record with a black and white cover photo of a man – him, actually – on coastal rocks. The picture was taken on Hirota cape 広田崎 and the record is called “Johnny Looking at the Sea” / 海を見ていたジョニー. Performed by Teru Sakamoto Trio 坂元輝トリオ, this record now cost ¥100,000.

He played it on one of the gramophones. The first track, “Left Alone,” had a beautiful melody, made more poignant as the pendulum of the vintage Meiji-brand clock in the room swayed in the background.

There was also a comic book about yakuza which chronicled a brief episode featuring him and this record. A larger-than-life reprint of his illustrated face looked at us from the ceiling, with a little red ribbon knotted in his beard.

Despite speaking limited English, Terui liked to make puns in English and grinned like a boy when doing so. His toothy grin was just like that of his younger self depicted in the manga.

A local resident arrived later. He didn’t speak English. However, with the help of Google Translate, we managed to exchange a little bit. He remarked that it was an honour to interact with us as he would seldom encounter foreigners in Morioka.

I wish I could have replied that it was our honour and pleasure to have made their acquaintances. That we were grateful for their patience in communicating with us despite not having a language in common. Except for our shared appreciation for jazz.

Join the Conversation